Well friends, spooky season is almost upon us, and that means it’s time to get into the spirit of the season and get scared. And what better way to feel the reason for the season than summoning horrific entities from other planes to play children’s games?

Initially, I was going to run through several different games, but once again the research consumed me, so we are embarking on another multipart series (sorry not sorry) about urban legends and dangerous games to play in the dark…if you dare.

Some of these legends might sound familiar, some might be new, and some might have you wondering why a lot of these games seem fiscally irresponsible (but more on that later).

Are you afraid of the dark—of what might be lurking within the inky blackness?

Or are you the type of person curious enough to face your fears, step into the blackness, and see what awaits you?

Well, if you’re the latter, you’ve come to the right place, because today we’re going to learn how to play some fun little games that might give you a glimpse into what’s waiting for all of us in the dark.

I invite you now to turn out the lights, pause your Spotify playlist and silence the ambient noise that keeps you sane, and join me in darkness and the silence, so we can find out together, if there’s a very good reason to be afraid of the dark.

Now, it behooves me to give you a disclaimer before we delve into our dangerous games and the lore behind them. If you choose to play these games and dabble with the supernatural, you do so at your own risk.

Maybe nothing happens or maybe you’ll never be able to use your bathroom again.

For as long as man has walked the earth, humans have been seeking proof of the supernatural and unexplained, and they’ve also been really bored. That’s right, you and some weird Victorian kids had the exact same problem when you were seventeen and there was nothing to do on a Friday night. And that’s where folklore comes in.

Who among us hasn’t driven with friends out to some secluded part of their hometown to sit in a dark tunnel, drive down a creepy road, or head to an abandoned location to participate in an activity that would allegedly lead to some sort of supernatural interaction? And while participating in these local legends might not have led to anything more than a few laughs, were you not entertained?

But really, are you not entertained? (Gladiator, 2000)

People love stories, but more than that, they love stories they can engage with as a form of entertainment. And urban legends like the ones in your hometown, Bloody Mary, or the Elevator Game are all forms of interactive folklore. They allow us to collectively engage with familiar stories, build on them, and experience the thrill of a potential brush with something otherworldly.

So, let’s begin with an oldie but goodie—Bloody Mary, herself.

Now, there are several variations of how to play the game, but for the sake of brevity, let’s go with the most common:

What You Need To Play:

-

One incredibly dark room with a mirror. You’ll want to make sure the room is pitch black, so close any curtains or blinds.

-

A candle, match, or lighter. You could use a flashlight, but that feels a bit like cheating, doesn’t it?

-

A mirror you don’t mind having to throw away should a ghost reside in it.

-

While it’s not required, the traditional time to play Bloody Mary is between 11PM and 3AM. The vibes are important.

How To Play:

-

Screw your courage to the sticking place and go into the dark room alone.

-

Stand in front of the bathroom mirror and light your preferred source of light.

-

Peer into the darkened glass, and say “Bloody Mary” three times.

-

Gaze into the mirror and wait for Bloody Mary to appear.

-

If nothing appears in the mirror, blow out your candle, turn on the lights, and leave the room.

-

If Bloody Mary does appear, make sure you stay far away from the mirror (we hear she likes to grab). You can attempt to engage with her, but she doesn’t seem like the chatty type.

-

Bloody Mary may disappear on her own, and in that case, blow out your candle, turn on the lights, and leave the room. On the off chance she decides to stay, you’ll have to make a dash for the lights and blow out your candle as you flip on the lights. Now, get the hell out of dodge.

-

Now, in theory, Mary will have left the mirror, but who is to say a door once opened is ever truly closed? I suppose you could keep the mirror, but honestly, if you see a dead woman covered in blood pop up in a mirror, you should probably wrap that mirror up and dump it in the ocean.

Now, you might be asking yourself, who the hell is going to show up if I play this game, and the answer is a bit complicated.

You see, there are many Marys out there, and quite a few with a grudge, so it’s hard to say who exactly you’ll summon. And that’s the thing about Bloody Mary, it’s not so much a game as it is a summoning ritual that’s loosely based around scrying.

What is scrying exactly?

Scrying comes from the Old English word, “descry,” which loosely translates to “catch sight of” or “make out dimly”. There are many different ways to scry, but the most common are peering into dark water or obsidian mirrors in order to make out shapes or see visions. It is often used as a form of divination, but can also be used as a tool to communicate with spirits.

And what is Bloody Mary if not looking into a darkened mirror, hoping to make out something in the glass?

In many folkloric traditions, mirrors are seen as portals, which is why they can be used as a tool to summon and communicate with spirits. While obsidian mirrors are preferable, as Ina Garten would say, a store-bought mirror in a dark room is fine.

So, if theoretically, mirrors are portals, when we call out “Bloody Mary”, we are summoning something to communicate with via this gateway. The question then is, who are we summoning?

Well, there are a few guesses as to who Bloody Mary could be.

The most likely suspect is the woman remembered affectionately by history as “Bloody Mary” or Mary Tudor.

Portrait of Mary I by Antonis Mor (1554). She looks like she could fuck a bitch up through a mirror.

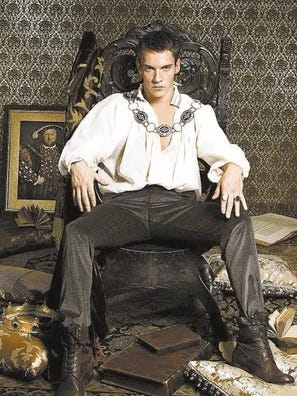

Not to get too deep into the weeds of the British monarchy, but Mary Tudor had it pretty rough growing up. And while you might not be as familiar with Mary, you’ll certainly remember her famous father, forever immortalized on screen by Jonathan Rhys Meyers, King Henry VIII.

Remember when period pieces used to just be sexy? I do. Can you believe I watched this show with my mom? (The Tudors, 2007-2010)

The actual King Henry VIII. This was later in life, of course, but you can see the liberties taken with casting (Portrait of Henry VIII by After Hans Holbein the Younger…yes that is his real name).

Now, those of you familiar with Henry VIII know he was famous for three things:

-

Taking credit for writing that absolute banger of a tune Greensleeves.

-

Beheading multiple wives.

-

Being obsessed with producing a male heir.

Mary Tudor was the daughter of King Henry VIII and his first wife (known for keeping her head), Catherine of Aragon.

A strange and haunting portrait of Catherine of Aragon and a monkey by Lucas Horenbout (1525).

Catherine and Henry had a somewhat unusual start to their marriage. The Spanish Princess was actually brought over to England to marry his elder brother, Prince Arthur of Wales, the firstborn of King Henry VII and heir to the British throne. As part of a bid to cement an alliance between Spain and England, Arthur and Catherine were married in November of 1501, but their marriage was to be short-lived.

A month after the wedding, the couple moved to Arthur’s estate in Wales, Ludlow Castle. Sometime in March of 1502, the couple contracted an unknown illness, and while Catherine recovered, Arthur died barely a month later in April of 1502.

Reluctant to lose an alliance with Spain, a plan was devised between King Henry VII and Queen Isabella of Spain to marry Catherine off to Arthur’s younger brother, Henry. There was one tiny problem though—Catherine and Arthur had already consummated their marriage…or did they?

We may never know for sure if Catherine of Aragon lied about her wedding night to receive a papal dispensation for an annulment, but we do know that Arthur was rather sickly even before leaving for Wales, and no one, save for Catherine’s chaperone stayed to witness the main event on their wedding night.

The marriage treaty was signed in 1503, but Catherine and Henry VIII would not wed until the passing of his father in 1509. Initially, Henry was reluctant to marry his brother’s widow, who was nearly five years his senior, but after ascending to the throne, he declared it was his father’s wish he married Catherine, and the two were wed shortly after.

Initially, Henry and Catherine seemed well-matched and rather happy in their marriage, but the pressure to produce a male heir would cause a growing rift between the couple that never seemed to heal. You see, Catherine struggled to carry to term. She had multiple stillbirths throughout their marriage, and the one prince she was able to carry successfully to term, died a mere seven weeks after his birth.

Catherine eventually gave birth to a healthy baby girl named Mary in February 1516, and tensions between the couple eased briefly. The couple finally had a healthy, surviving child, and Mary’s birth seemed to prove to Henry that Catherine was able to produce an heir…albeit not the right gender.

But, after the successful birth of Mary, Catherine had yet another stillbirth, and Henry began to wonder if he’d made a mistake marrying an older woman.

Henry was a known adulterer, who had many affairs during the course of his marriage to Catherine, and produced at least one publicly acknowledged illegitimate child with Elizabeth Blount, one of Catherine’s younger handmaidens. And that child was a boy, which served as some sort of proof for Henry that Catherine was the problem.

Now, it’s important to note that men actually determine the sex of the child. It’s also important to understand that miscarriages were not uncommon during this period, and while royals may have lived in better conditions than their subjects, they were still exposed to poor hygiene and unsanitary conditions (doctors were not really washing their hands the way they do now). Similarly, the ultra-religious Catherine was known to participate in rather extreme religious fasting during pregnancy, which also could have impacted her pregnancies.

And what did all this mean for Mary?

Well, when Henry decided to trade Catherine in for a younger model, he not only divorced Catherine, he claimed their marriage was illegitimate in the eyes of God because she had lied about consummating her marriage to his brother. This caused a big fuss in the Catholic Church, which was not interested in pissing off Spain, and ultimately resulted in Henry founding the Protestant Church of England with him as the ultimate authority.

And as the ultimate papal authority, Henry granted himself a divorce, annulled his own marriage, and went on to marry his second wife, Anne Boleyn.

Perfect angel Natalie Dormer as Anne Boleyn. (Tudors 2007-2010).

Catherine was stripped of her title, only allowed to retain the title she would have had as Arthur’s widow, Dowager Princess of Wales, and banished from Court. Mary was stripped of her title as well and declared illegitimate. She was not allowed to see her mother, and would eventually be shipped off to live at her baby sister, Elizabeth’s, estate as a pseudo member of her household.

In 1536, Catherine of Aragon died from what historians now believe was cancer. Mary was forbidden to see her mother, even in the days leading up to her death. Not long after Catherine’s death, Elizabeth would join Mary in illegitimate child limbo, when her mother fell out of favor with the King and lost her head.

Over the years, with the help of her stepmothers, Jane Seymour and Catherine Parr, Mary would somewhat reconcile with her father and eventually be deemed legitimate and rejoin the line of succession. But, despite eventually returning to her position and her father’s good graces, Mary would not forget the way she and her mother were cast aside, nor would she forget what, in her opinion, started this whole mess: Protestantism.

In 1574, Henry VIII finally died. It was great news for his last wife, Catherine Parr, whose head was close to being on the chopping block, but not entirely great news for Mary. According to the Act of Succession 1544, though Mary was in line for the throne, her nine-year-old half-brother, Edward, had first dibs.

Henry had allowed for the Church of England to remain essentially Catholic. He rejected all papal authority, but didn’t really feel a need to uphold all the tenets of Protestantism; however, Edward felt differently. Under Edward’s rule, a true Protestant Reformation occurred, and his devout Catholic sister, Mary, was under pressure to convert. But, Mary, would not abandon her Catholic faith and continued to practice in secret.

Edward’s reign was short-lived. At the age of fifteen, he contracted a rather serious lung infection and passed. Before his death though, he grew concerned about Mary taking the throne and consulted with his advisors on how to ensure the throne would not go to a Catholic. Both Mary and Elizabeth were removed from the line of succession, and his cousin, Lady Jane Grey, was named his successor.

But, Lady Jane would not be queen for long (nine days in total). You see, Mary had it up to here with the Tudor men and decided to amass supporters and an army. Two days after Jane ascended to the throne, Mary had amassed an army of nearly twenty thousand supporters and things quickly fell apart for the new regime. Barely a week passed before, Lady Jane was deposed and imprisoned in the Tower of London for treason.

On August 3, 1553, Mary, accompanied by her sister, Elizabeth, and 800 nobles, rode into London and took back the throne, but unfortunately for Mary, her story doesn’t end there.

At this point, Mary was nearly thirty-seven years old and still unmarried. Though her advisors begged her to marry British nobility, Mary was determined to renew a connection with the Hapsburg family and married her cousin and a man nearly ten years her junior, Philip II of Spain.

Once the two had wed, Mary was desperate to conceive an heir to change the line of succession. Elizabeth, would not convert to Catholicism, and Mary was not keen to allow the throne to fall into Protestant hands again.

Mere months after her nuptials, Queen Mary began to show signs of pregnancy. She’d stopped menstruating and felt nauseous during the day. Her breasts were swollen, her clothes no longer fit her, and a telltale baby bump appeared. Mary was believed to be due in late April of 1555, and six weeks before she was believed to be due, she entered her confinement.

For those unfamiliar, confinement is a thankfully outdated practice we no longer force pregnant women to participate in. Confinement typically began four to six weeks before the due date and required the woman to be “confined” to her rooms to ensure a safe delivery. Prior to the Tudor era, confinement was not necessarily a bad scene, women used to be able to hang out with friends and enjoy fresh air and exercise, as long as they did not leave their chambers.

However, King Henry VII’s mom decided that was a bit too whimsical for her taste and implemented her own rules for what a Queen’s confinement should look like. Windows were boarded up, so no light or fresh air could get in; furniture, save for a bed, and books were removed so the mother-to-be could focus solely on resting, and no men were allowed inside the room, even the woman’s husband or male family members.

Now, some of you might say, it sounded like King Henry VII’s mom hated his wife (spoiler: she did), and assume it would be ridiculous to continue this horrific practice, but unfortunately, the practice continued.

Mary did not do well during her confinement. The female courtiers in her retinue who were permitted to visit reported finding Mary weeping for hours in the fetal position or rocking back and forth on the floor, mumbling to herself. Then, when April had passed and no child was born, her physicians grew concerned.

At the end of April, there was a report circulated that the Queen had given birth to a boy. We’re not sure where this news originated from, but the people began to celebrate their future king. But, as May turned to June and no child was presented before the Court, people began to wonder if there really was a child or if the Queen had miscarried.

Mary began to insist it was the doctors who had erred in their estimation of the due date and promised those around her the child would be born by July. It was sometime around this point that Philip began to publicly express to close family members his doubts that Mary was actually pregnant. It’s not clear if he ever shared these concerns with Mary, but we do know her increasing instability and insistence she was pregnant had become a strain on their relationship.

July came and went, the slight “baby bump” disappeared, and Mary’s depression worsened. By August, Mary was forced to leave her confinement and admit to the world there was no baby. She was thin and sickly from refusing food for months, and humiliated by the rumors that began to swirl during her confinement, that she’d birthed some sort of abomination—a dog, a monkey, something unnatural and ungodly.

Philip, by this point, had grown weary of Mary, and by the end of September 1555, he’d decided that he’d rather go off to war than offer support to his seriously depressed wife.

Once again, Mary was alone.

And despite everything she’d overcome and her faith, she’d wound up in the same position as her mother—unable to bear an heir, and quickly losing the love of her King. Mary began to believe she was being punished by God for allowing Protestantism to remain in England, and began a reign of religious terror that earned her the moniker “Bloody Mary”.

Well, that’s not exactly true. It would be easy to say this traumatic event was what spurred Mary to revive the heresy laws that led to nearly three hundred Protestants burned at the stake, and forced close to eight hundred Protestants to flee into exile to avoid the same fate, but the truth of the matter is that Mary began to pursue Protestants barely a month after taking the throne.

You see, Mary had to lie a bit to usurp Lady Jane Grey. She needed support from more than just the remaining Catholic nobles; she needed the power and purse of the Protestants as well. So, she fed them a little white lie and promised to leave the Protestants alone when she took the throne. Unfortunately, they believed her.

Once Mary was crowned, she pushed Parliament to repeal her father’s religious laws in order to give Rome power over the British state once more. She swiftly began imprisoning prominent Protestant leaders, and by February 1555, months before she was to give birth, she’d worked with the Pope to reinstate a revival of the Heresy Acts, which gave the Church and the monarchy the ability to try, imprison, and execute perceived heretics.

Mary had always planned to purge England of Protestantism, which is why those familiar with her story know there were multiple attempts to remove her from the throne in favor of her sister, throughout her reign. She was deeply disliked by her people, who were tired of religious persecution and the fact they were tied up in Spain’s disagreements with France, which ultimately meant they would be funding another war.

So, the false pregnancy, along with a husband more interested in war than supporting his grieving wife, and a country filled with people mocking her for being a crazy, barren woman, merely validated her beliefs. God was testing her, and unlike her mother, she would not give up.

This is where things get a bit dark.

Normally, when a “heretic” was tried, they were offered an opportunity to renounce their faith and convert to the “true faith”, Catholicism. But, Mary was no longer interested in conversion to the “true faith”; she wanted to see heretics burn.

And burn they did.

In March of 1556, the imprisoned Archbishop of Canterbury was dragged from prison to stand trial for heresy. He’d been forced to watch two of his close friends, Bishops Ridley and Latimer, be burned alive, and publicly renounced the Protestant faith to save himself from the flames. But, it was too little too late for the Queen, and the Archbishop was tied to a stake and forced to suffer the same fate as his friends.

Mary saw her husband one last time in 1557 when he briefly stopped by to ask for more money so he could continue his war. We don’t know if the two actually shared a bed or if Philip’s trip was business only, but by the time Philip was gone, Mary was convinced she was pregnant once again and announced her condition to the Court.

Once again, Mary experienced symptoms of pregnancy: she stopped menstruating, her abdomen distended, she began to gain weight, and experienced morning sickness almost daily. A nursery was prepared, new staff was brought on in anticipation of the new addition, and Mary was once again happy. But, when the baby, due in March of 1558 had failed to appear by May of that year, Mary was finally forced to admit there would never be a child.

Mary never recovered from the realization of her second phantom pregnancy. She fell into a deep depression and stopped sleeping. Her body began to retain fluid and her flesh grew swollen. She was plagued by headaches, periods of confusion, and abdominal pain.

In November of 1558, an influenza epidemic took the country, and unfortunately, the already ill Queen contracted the virus. By November 17, Mary was practically blind, feverish, and barely able to stay conscious. She died later that day, but not before telling her attendants about the fever dreams she’d been having of all the children waiting for her, playing and singing around her.

After her death, Philip returned to Spain, and her Protestant sister, Elizabeth, ascended to the throne thus ending "Bloody Mary’s” reign of terror.

Elizabeth had seen what marriage had done to the women in her life. Her mother had been beheaded the minute she’d lost favor with her husband. The same man who cast out his wife of over 20 years, beheaded his fifth wife and would have killed his last if he’d not died first. Women who were scorned for not producing an heir or not producing one of the right gender or were hated by the men around them for simply having ideas.

She watched her sister go mad with grief merely because she couldn’t get pregnant. And she’d watched her sister’s husband abandon her, returning only when he needed money because Mary’s grief was inconvenient.

No, Elizabeth would never marry. She would never allow a man to determine her fate.

Despite everything that had happened between the two sisters in life, Elizabeth made sure her sister was given a burial befitting of a Queen of England. Mary was interred in Westminster Abbey in a tomb she now shares, not with her mother or husband, but with her sister.

There is an epitaph upon their tomb that reads: “Partners both in throne and grave, here rest we two sisters, Elizabeth and Mary, in the hope of the Resurrection.”

And while the tomb for two was a decision made by Elizabeth’s successor, King James I, at the very least, Mary is no longer alone.

Is it possible that Bloody Mary summons the soul of the dead Queen?

It’s true that Mary was bloodthirsty in life for Protestants, but her death was ultimately peaceful. She died dreaming and believing that what eluded her in life awaited her in death. And Elizabeth had promised Mary that she would not treat Catholics the same way Mary had treated the Protestants (though how well she kept her promise is debatable).

Queen Mary I is a complicated figure. Her mother was taken from her, and her father’s love was conditional. She had stepmothers like Catherine Parr and Jane Seymour who cared for her, and she had others like Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard who were disinterested in her existence. She married a man who saw their marriage as political and her as a blank check.

And though she loved her brother, Edward, and her sister, Elizabeth, their differing views on faith made their relationship a challenge. Mary particularly struggled with her feelings over Elizabeth during her reign, as though Elizabeth did not openly plot against her sister, she was the figurehead of many a rebellion who sought to overthrow the tyrannical Catholic Queen.

It’s hard to imagine though that Mary would be a vengeful spirit as opposed to a mournful one, despairing over the love and the family she never truly had in life.

So, is there perhaps a better contender for who Bloody Mary could be?

In some versions of the story, Bloody Mary is famed serial killer Hungarian Countess, Elizabeth Báthory (Erzsébet Báthori), also known as the “Blood Countess”.

Unfortunately, there are no contemporaneous paintings of Elizabeth, only one that was painted almost 100 years after her death that is believed to be a slightly altered copy of another painting. So please enjoy this still of Anna Friel, from a movie I had no idea existed and I’m sure is fully factual (based on the the description stating it is a true story), Bathory: Countess of Blood (2012).

Elizabeth’s story is one you may be familiar with—the story of a vain, sadistic woman terrified of losing her youth.

The legend goes that Elizabeth was a vain young woman, who spent nearly half the day preening and dressing for her husband. One day, as she nearly finished getting ready for the day, a young servant girl pointed out a mistake with the way the Countess’ headdress was fashioned. Annoyed by the error and the girl’s insolence, Elizabeth slapped the young girl so hard, that blood spurted from the servant’s nose onto Elizabeth’s face and neck.

Initially disgusted, Elizabeth raced to wipe the blood away, but realized, as she did so, that the skin the blood had touched was softer and more supple. It made her complexion more even and pale, and strangely more youthful. It was at this moment, the Countess resolved to incorporate blood into her daily beauty routine.

Now, it just so happens that, Elizabeth’s husband, Count Ferenc Nádasdy, was a connoisseur of torture and torture devices, and felt it was important to educate his younger wife in the ways of sadism.

Elizabeth had no shortage of tools to trap and string up her victims, but if she was going to bathe in blood every day, she needed more than a few servant girls. So, she and her four most trusted maids concocted a plan. They would lure the unwed daughters of peasant families to the Countess’ home, under the pretense of offering them work.

Once the girls arrived at the castle, they would be taken to Elizabeth’s torture chamber where they would be bound and tortured by the Countess herself. She would whip, cut, and burn the girls, before eventually slitting their throats over a copper tub, so she could bathe for an hour each day in warm virginal blood.

After the death of her husband, Elizabeth, could no longer contain her bloodlust. She brought in more girls, some even the daughters of lesser noblemen. And on one occasion, when she was too sick to torture her captives, she attacked a young servant girl by sinking her teeth into her neck and tearing away the flesh to taste her blood.

But, Elizabeth had grown careless. People had begun to question the Countess’ strange behavior, especially her almost deviant obsession with young women. They wondered why so many girls entered the castle, but only coffins ever seemed to leave. Eventually, the rumors grew to such a fever pitch the King himself was forced to investigate.

The Countess’ crimes were revealed, and nearly six hundred and fifty girls were found dead. As punishment, her four accomplices were executed, but the King had something else in mind for the Blood Countess.

Elizabeth was taken to her rooms, which sat in the highest tower of her castle. She would be allowed to live, but she would never be allowed to leave. She would be bricked into her rooms, forced to live on, and watch herself wither and age without her blood.

And that’s the story of Elizabeth Báthory…or so they say.

It’s easy to believe that a sadistic woman obsessed with bathing in blood to achieve eternal youth would be a perfect candidate for Bloody Mary. After all, Elizabeth was locked away and forced to watch herself age. It would make sense for her to be angry, to want blood, and to be connected to mirrors.

There’s just one problem…her name isn’t Mary.

And there’s one other very tiny issue…

It’s pretty likely this whole Blood Countess thing is a complete work of fiction.

You see, there’s a lot the folklore around Elizabeth tends to ignore. Like the fact that as a widow, she was one of the wealthiest and most powerful nobles and that the King of Hungary happened to owe her quite a lot of money.

So who was the real Elizabeth Báthory? Let’s find out.

Elizabeth was born in 1560 into the noble House of Báthory.

The Báthorys were an incredibly well-connected family with two distinct lines: the Somlyós and the Ecseds. Elizabeth’s father, George of the Ecsed branch of the family, was a Baron, and his brother was the ruling Voivode of Transylvania. Her mother, Anna of the Somlyó branch, was the daughter of the Palatine of Hungary and niece to the Prince of Transylvania, who would eventually become the King of Poland and the Grand Duke of Lithuania.

Elizabeth grew up in the town of Ecsed, presently known as Nagyecsed, in her familial castle. Unlike most girls of the time, Elizabeth was provided a serious education and would go on to become one of the most well-educated women of her time. She could read and write, spoke several languages, and had a penchant for philosophy.

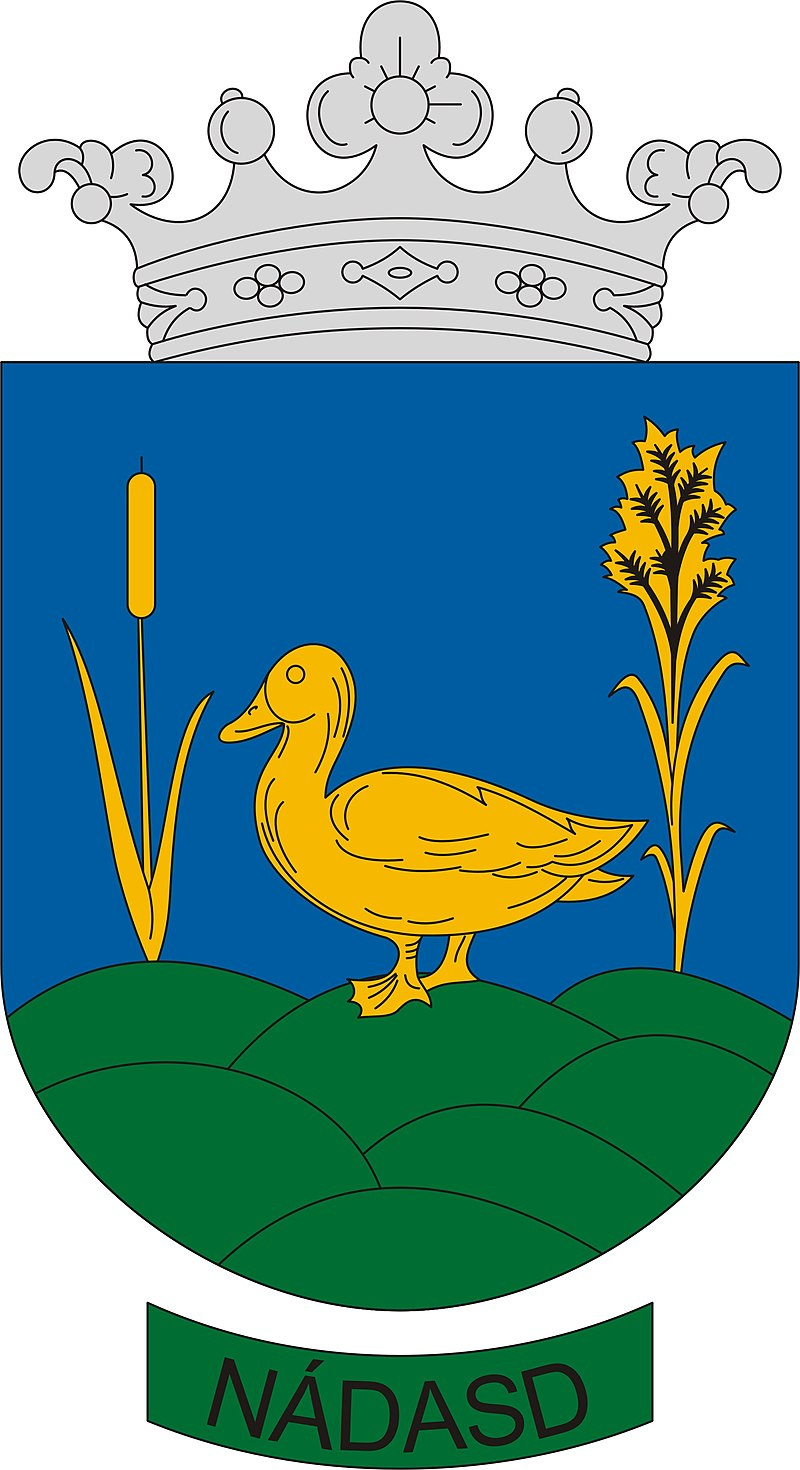

Though Elizabeth was known for her beauty, it was the power her influential family wielded that made her a true prize in the eyes of suitors. But, the Báthorys did not want Elizabeth to marry just anyone; they wanted to ensure her marriage would benefit them and sought to form a strategic alliance with the powerful and wealthy Nádasdy family.

It’s important to note that this marriage was a highly political move by both families that gave them control of a significant amount of land in both Transylvania and Hungary. The combined wealth and power this marriage brought would have been seen as threatening to other noble families, and even the King of Hungary himself.

I would just like to take this moment to show you the coat of arms of the noble House Nádasdy. I was truly floored to find that people who chose a duck to represent their noble house went with the motto, "If God is for us, who can be against us?".

Around the age of twelve, Elizabeth was officially betrothed to Count Ferenc Nádasdy, three years her senior. They were officially married in 1575 and the couple was gifted the Castle of Čachtice (Csejte) and seventeen surrounding villages as a wedding gift.

Not much is known about the relationship between Elizabeth and Ferenc. We know they had little in common, Ferenc could barely read and write and was more interested in the life of a soldier than that of a philosopher. We also know it took them ten years to conceive their first child.

I suppose it’s easy to see why it took ten years (Portrait of Ferenc Nádasdy by E. Widenman 1656).

As a military man, Ferenc was away from home for a significant amount of time, and barely three years into their marriage he was appointed Chief Commander of the Hungarian troops and was sent to fight the Ottomans.

While Fenrec was on the front lines, eighteen-year-old Elizabeth was not only left in charge of the castle and various villages and estates; she was also in charge of her husband’s business affairs, providing medical care to wounded soldiers, and defending Čachtice, which stood as the lone protector on the road to Vienna. But, whip-smart Elizabeth was more than up to the task and dutifully managed her husband’s affairs while he was away.

In 1585, the couple welcomed their first child, Anna. They would go on to have four more children, though it is suspected that Elizabeth suffered several miscarriages or stillbirths throughout her life, as there are at least two other children mentioned in documents that never appear in her formal will.

And things were good for the most part until Ferenc died in January of 1604. On his deathbed, he entrusted the care of his wife and children to his friend György Thurzó, which was a mistake on his part as Thurzó would go on to lead the charge to investigate Elizabeth’s alleged killing spree.

Now, before we dive in, it’s important to understand that this is where things get murky--mainly because so much of what we know about Elizabeth comes from lore circulating at the time.

Here is what we know for sure:

After Ferenc’s death, Elizabeth inherited his wealth and his lands and held a great deal of power in her own right. There were rumors around this period of missing servant girls and Elizabeth’s sadistic cruelty, but no formal complaints were ever made and the veracity of these stories is questionable.

In 1609, Elizabeth created a gynaeceum or “academy for young women” of noble blood, which was intended to serve as a sort of finishing school for noblewomen to prepare them for married life. Sometime around this period, tales of coffins leaving the castle in the night began to crop up, and in late 1609, a Lutheran minister by the name of István Magyari made public complaints against Elizabeth, claiming she was torturing and killing young women in her home.

In response to Magyari’s claims the King charged György Thurzó, a former friend of Elizabeth’s husband and current Palatine of Hungary, with investigating these alleged crimes. Thurzó is said to have interviewed over three hundred witnesses who claimed to have seen Báthory’s sadism firsthand, interrogated her four closest attendants who admitted to helping her slaughter young women, and searched Elizabeth’s castle for evidence and found at least one dead servant girl and a tortured girl who was still alive.

Now, though it might seem like a slam dunk of a case against Elizabeth, that’s not quite the full story. You see, those “witnesses” Thurzó interviewed didn’t actually witness anything. Most of the witnesses ultimately admitted they were repeating stories they had heard from friends and relatives.

Such as stories of naked women being slathered with honey and eaten alive by bugs; stories of naked women being forced to take ice baths in the cold; stories of the Countess pricking, cutting, and biting women (who were probably naked); and the list goes on. And, you may be thinking, it’s strange that most of these anecdotes sound like weird lesbian torture porn, and you would not be wrong in that assumption.

There is something peculiar about the homoerotic nature of many of the accusations against Elizabeth Báthory, which seem to paint her as not only a sadist but a predatory lesbian, stealing away young women. But, we’ll return to this later.

And the four attendants?

Well, after being tortured for hours, they eventually agreed to whatever Thurzó told them to.

As for the body that was allegedly discovered, we don’t have any additional information. It’s possible that Elizabeth killed a servant and it’s also just as likely that a staff member contracted a disease or simply died of natural causes, and they were waiting until the winter frost melted to bury the body. And whether there was a tortured girl found during the search is also debatable, as there seems to be no evidence this girl ever offered any testimony (or even existed).

Thurzó’s story also changes at some point, and whether it was his own embellishment or the story slowly becoming a tall tale, we can’t be sure, but the single body eventually turns into a horror dungeon with naked women sliced to ribbons and strung up like cattle.

In the end, it was decided it would be best not to have a formal trial. We don’t necessarily know for sure why they opted to avoid a trial. Perhaps they wanted to preserve her dignity as a noblewoman, perhaps there was significant pressure from Elizabeth’s family to avoid a public scene, or perhaps there simply wasn’t enough real evidence to convict the Countess.

Regardless, Elizabeth’s four attendants were executed for their alleged participation in these crimes, and Elizabeth was forced to live out the rest of her life as a prisoner in her own home, sealed into her personal quarters with only a small slit for fresh air and to receive her meals.

On August 20th, 1614, Elizabeth spoke to one of her guards through the small “slit” in the wall and told him her hands felt cold. Reportedly, the guard told her she would be alright, before finding her corpse the following day.

Elizabeth Báthory died a criminal in her own home, but was she the sadistic villain everyone believed her to be?

There’s been a lengthy scholastic debate over Elizabeth’s crimes, with many scholars believing she was likely framed by Thurzó and the King. You see, the King of Hungary just so happened to owe Elizabeth a hefty debt that was miraculously cleared by her remaining relatives once she was imprisoned. Thurzó and several of her distant family members also benefited from her “conviction”, because when Elizabeth was imprisoned (an imprisonment curiously managed by these same relatives), her children were exiled from the Hungarian Empire and forced to relinquish any claim on their inheritance.

It’s possible this was all a political scheme; however, University of Cambridge academic Dr. Annouchka Bayley (a woman who has dedicated her life to vindicating Báthory) has a different theory—one that revolves around Elizabeth’s gynaeceum.

Bayley found something particularly interesting during her extensive research into Báthory’s story—the gynaeceum was no mere finishing school, but a place for women to learn to read and write, and encounter ideas from Reformation Europe. Even more peculiar, Elizabeth had a printing press in one of her other castles in Sarvar.

Perhaps, Elizabeth was merely a collector of interesting items like printing presses or perhaps it is no coincidence that the highly controversial writings of the Spanish scholar, Michael Servetus, appeared in Transylvania during Báthory’s reign.

Was Elizabeth a psychotic woman with a penchant for blood or was she, as Bayley argues, merely a radical trying to educate women?

It’s interesting that a minister of all people filed the initial complaint, and not one of the six hundred families whose young girls allegedly went to stay at Castle Čachtice, never to be seen again. Was the minister simply a concerned citizen trying to protect the young women of Hungary? Or was Elizabeth caught doing something the Church would have disapproved of like sharing “radical” Unitarian ideas?

Remember how earlier we talked about how weird all the stories circulating about Báthory were and how they all were giving lesbian torture porn energy? Well, it might be proof that Bayley was onto something with her theory.

You see, if Elizabeth really were a radical, preaching freedom from religious and gender-based oppression, you’d probably want to make sure nobles thought twice about sending their daughters to stay with some noblewoman. Perhaps you’d want to make the noblewoman out to be more than just a monster; maybe she was a sadistic sexual predator as well who preyed upon virginal young women.

There is one more bit of evidence that gives credence to Bayley’s theory that Elizabeth Báthory might have been a bit of a radical.

A printing press was discovered at the second castle she and her husband owned. It’s a rather peculiar thing though, for a noble couple to have lying around, but Bayley believes it was no mere curio. She posits that Elizabeth may have been printing and transporting pamphlets of banned works like Spanish scholar, Michael Servetus’, Christianismi Restitutio, which decried the idea of a “Holy Trinity” in favor of true monotheism, and pushed for Western Christian civilizations to engage with science or risk being overtaken by the scientifically advanced Ottomans.

It’s possible Bayley is correct in her assumption, as strangely, copies of books like the Christianismi Restitutio seemed to reappear in Transylvania around this period.

And how did Elizabeth transport these pamphlets?

When Dr. Bayley visited Castle Čachtice, she found an intricate series of tunnels under the main structure. It’s possible that Elizabeth used these tunnels to transport contraband, and the “coffins” people swore they saw coming out of the castle and disappearing in the night were nothing more than boxes of banned books.

Bayley’s theory makes a lot of sense when you consider the sole complaint against Elizabeth was filed by a devout minister, and that the case against her is piecemeal at best. Of course, people may have wanted debts forgiven and a piece of the pie, but it’s curious that Elizabeth’s punishment was ultimately to be monitored 24/7 and have her access to the outside world cut off.

Sure, you can say the lack of a trial and quiet punishment was out of respect for her family and because she was a woman of noble blood, but I would argue that if there truly was a woman ripping throats with her teeth and bathing in blood, they wouldn’t have wrapped things up so quickly.

Between 1520 and 1780, there were over 1,600 documented cases of individuals being put on trial for witchcraft in Hungary, and there are potentially hundreds of undocumented cases we have no record of. It seems odd to me during a time when people were quick to label others as witches that somehow draining the blood of virgins to attain eternal youth wouldn’t be considered witchcraft. In fact, witchcraft was never mentioned in the Crown’s case against Elizabeth.

And the question is, why not?

Because if Báthory really did kill over six hundred women for her skincare routine, why not label her a witch and achieve the same outcome? Surely the King and her relatives could have come to the same arrangement were she executed. So, was it because she was a noblewoman afforded special privileges? Or was it because Elizabeth was caught teaching young women radical ideas and distributing banned books?

Curiouser still, multiple priests visited Elizabeth during her confinement and thought it was odd that she was not bricked up into a room like the stories said. They all remarked that she seemed to wander about the castle freely, though monitored by guards.

All of this is not to say that Elizabeth never punished her servants or behaved cruelly. The late 1500s to early 1600s was not a period known for “workers' rights”. Corporal punishment was commonplace and there were few consequences for nobles that took things too far. It’s certainly possible Elizabeth or her husband beat or whipped a servant to death at some point, just as it’s equally probable servants died from unsanitary conditions and communicable diseases.

Now the real million-dollar question, where did all this stuff about bathing in blood and vampirism come from?

I would hazard a guess that Elizabeth herself may have had a hand in the creation of her own mythos.

A fact people often fail to mention is that Elizabeth suffered throughout her life from epilepsy, known at the time as “falling sickness”. And the remedy for “falling sickness” in the 1500s was to rub the blood of a non-sufferer on the lips of the afflicted. Sometimes blood was rubbed as the episode ended, and other times blood was used preventatively to stop episodes before they arose.

It would not have been uncommon for people to see Elizabeth rubbing blood on her lips or keeping a vial on her person or with an attendant. And as her condition was not widely known, it would have been easy to conflate this odd behavior with something far more sinister, like a thirst for blood.

Elizabeth was likely aware of the rumors surrounding her use of blood and decided to capitalize on it.

After all, she spent the majority of her married life with her husband hundreds of miles away, fighting back the Ottomans, in a castle that served as the final barrier between invading armies and Vienna. What better way to ensure the safety of herself and her children than to become someone whose reputation for cruelty and bloodlust preceded them?

The fact of the matter was that after her husband’s death, Elizabeth did not have the same level of political clout or protection she had when she was younger. Her uncles were no longer the Palatine of Hungary and Prince of Transylvania respectively, and her elder brother, the former Judge Royal of Hungary, had died shortly after her husband. It was also well known that the Countess was a widow, living in a remote area.

What better way to protect herself and her land than by becoming someone people feared, not just because of her wealth, but because she was something truly monstrous?

Consider how far the story of the Blood Countess had circulated in just her own lifetime—how everyone had heard stories of the sadistic Countess, but no one ever actually witnessed any of these crimes, and ask yourself, if it was truly a mere coincidence that these stories began to circulate around the time Ferenc died…

So, is Elizabeth Báthory who we conjure when we chant Bloody Mary? Or is she simply another maligned woman?

I would argue that based on what we know, it’s quite unlikely the real Elizabeth is anything like the Elizabeth Báthory of folklore. And though she might want revenge on those who imprisoned her, I think, more than anything, the end of her life was colored more by loneliness than rage.

Elizabeth went from a castle full of young, eager pupils to an empty home with no one she could engage with. The close attendants she’d spent years of her life with were dead, and she died without ever being able to see her children again.

I would think if the real Elizabeth was summoned, she would more likely want companionship than blood.

Now, we’re not done with Bloody Mary quite yet.

We have one more Mary to cover and a shot in the dark at who we might really be summoning when we chant her name three times in front of a mirror.

Part 2 of our deep dive into the real Bloody Mary is up and remember, if you decide to play her game, keep a safe distance from the mirror (she’s a grabber).

Stay cursed, friends.

Resources:

Catherine of Aragon by Luz Santodomingo & Samuel Yelton

Elizabeth Báthory: The Hungarian Countess by Pressley Reeve

Fires of Faith: Catholic England Under Mary Tudor by Eamon Duffy

Investigating Elizabeth Báthory: Hungary's Infamous "Blood Countess" by Kristen Ford

Mary Tudor: The First Queen by Linda Porter

New exploration of “Countess Dracula” reveals a 17th-century radical whose crimes were faked by Cambridge University Faculty of Education

No Blood in the Water: the Legal and Gender Conspiracies against Countess Elizabeth Bathory in Historical Context by Rachael Leigh Bledsaw

The Alleged Miscarriages of Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn by Sir John Dewhurst

The Illness, Death, and Burial of Mary I by Tudor Extra

The Queen’s Quickening: The phantom pregnancies of Mary I by Eve Elliot